Weak Regulations, Fatal Syrups

Governance failures in quality assurance in

Indian pharmaceuticals need immediate resolution

T Sundararaman writes:

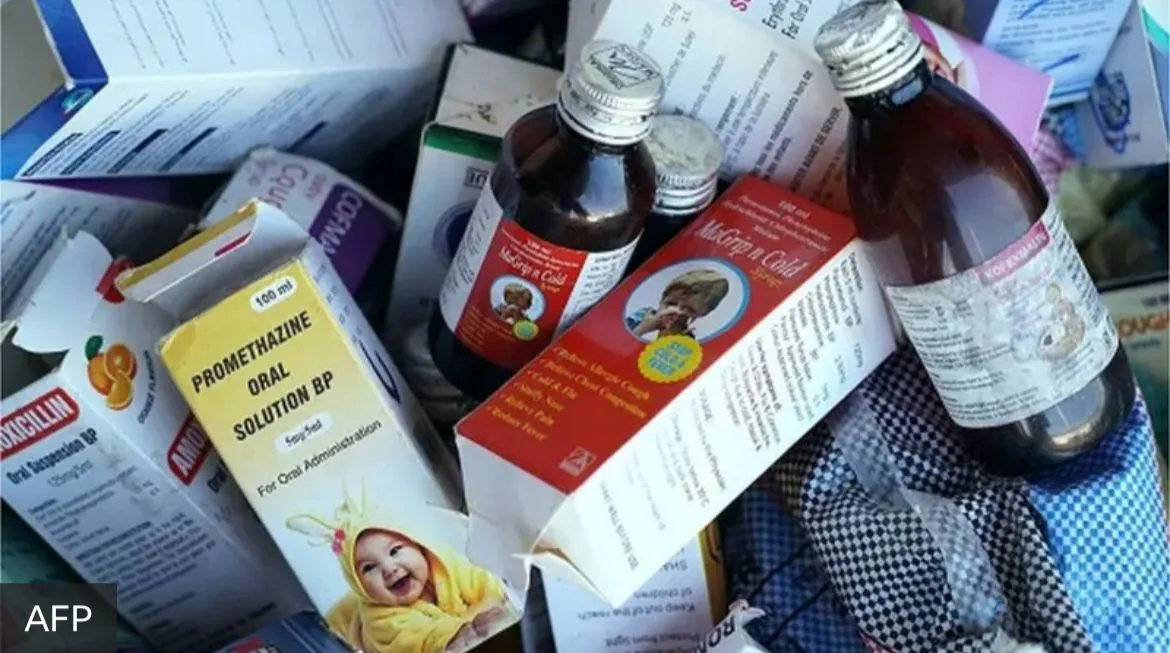

In September–October 2025, over 24 children in Madhya Pradesh (MP) and three in Rajasthan lost their lives due to consumption of cough syrups that contained toxic levels of diethyleneglycol, a poisonous industrial solvent. This tragedy is all the more appalling as there have been many similar episodes of child deaths in India in the past, all with the same toxin. In 2022, child deaths traced back to poor-quality pharmaceuticals manufactured in India were reported in Gambia and Uzbekistan. The government’s response is an immediate raid and delicensing of the specific manufacturer and sometimes an arrest. But these seldom lead to trials and convictions. After a flurry of media stories and some placatory statements by the political leadership, the issue was forgotten.

This time around, a medical doctor in MP, who had prescribed the medicines, was arrested, much to the legitimate chagrin of the entire medical association, for clearly there was no way an individual doctor could know which medicine on the market contains substances not on the label that can cause injury or death. The assumption that all doctors have to go by in their daily practice is that every single tablet and bottle of medicine sold in a pharmacy is of adequate quality, and there is someone somewhere who is responsible for ensuring this. The directive principle of governance for pharmaceutical markets should be that all medicines sold in the market must conform to quality standards as prescribed, irrespective of brand, price or source. This requires a regulatory system that has the capacity for quality assurance at every step of the manufacturing and distribution process and, that can fi x accountability for substandard and spurious drugs, not only on the manufacturer’s part but also on the gaps in the regulatory chain.

Such a directive principle is all the more relevant and urgent, because deaths due to poor-quality medicines are invariably the tip of the iceberg. Far more frequent manifestations of poor quality are therapeutic ineffectiveness, excessive side effects, and reduced quantity of the active pharmaceutical, as against what is stated. Such defi ciencies cannot be detected by the patient or the provider or even the dispensing pharmacist. There is no evidence to believe that a greater reliance on popular brand names or global brands will ensure better quality of medicines. The perceptions of comparative quality across brands more often refl ect successful marketing strategies rather than any assurance of quality.

Quality assurance in medical products is a public good which markets cannot deliver. Only an enforced protocol of quality assurance across all pharmaceuticals on the market can reliably ensure quality, and that is a major function of any government. The Central Drugs Standard Control Organisation (CDSCO), India’s central drug regulatory authority, does put up on its website longlists of drugs on the market found to be substandard by state and central drug inspectors, but it is not clear how many of these are minor procedural gaps and how many are major gaps that require a product alert across the country. And why are the numbers of such violations so high and so persistent? Clearly, these are only indicative of tragedies waiting to happen.

Governance failures in quality assurance are not only a danger to individual’s health but they are also a major threat to the national economy. Such instances would turn global perception against the “made in India” label. We should not be surprised if global competitors make use of this opportunity to discredit Indian pharmaceuticals. India’s domestic industry is already reeling under pressures due to increasing tariffs and non-tariff barriers and it can ill afford any doubts raised on its quality assurance. A general scepticism about the quality of India’s pharmaceuticals is particularly unfair to an industry where most manufacturers have taken considerable efforts to ensure quality products. Without this, we could hardly have become the pharmacy of the world.

We must recall that India still has the largest number of United States Food and Drug Administration (USFDA)-approved plants that any country has, and our generics are bought by countries with the strictest drug quality standards. A public perception that associates quality with higher prices, branded drugs and multinational manufacture will necessarily make medicines much less affordable, and this will, in turn, decrease access to essential medicines in both the public and private sector. So clearly, it is unacceptable to allow an erring and incompetent subset of Indian manufacturers to damage the reputation of the entire industry, compromise public health interests, and cause harm to individuals.

Since the mid-1990s, the Tamil Nadu Medical Services Corporation has shown that it is possible to design and operate an institution that can deliver quality assurance in a reliable manner, at very competitive rates, while assuring uninterrupted supplies across facilities. To ensure transparency, efficiency and quality, there is a minimum set of process requirements that have to be followed in procurement, distribution and quality.

Assurance. There are also protocols for ensuring the quality of the empanelled drug-testing laboratories, for taking action on firms supplying poor-quality medicines, including blacklisting them and even protocols for de-blacklisting, if they comply. No doubt, even these better systems have gaps that require improvement, but its great achievement is that it has demonstrated conclusively that access, affordability and quality can go together. Unfortunately, such a system is limited only to public procurement for public services. No similar system exists for drugs going into the private markets, where the “ease of doing business” is the dominant concern.

The government is clearly aware and seized of this issue. So, why does this governance failure persist? One major problem is the fragmentation of authority between the union and the states. At the level of the union government, the main regulatory institution is the CDSCO, which specifies the quality standards and provides marketing approval for new medicines and controls the quality of imported drugs in the country. Only recently has CDSCO taken on the role of quality assurance in exports, and it is still too early to comment on how effectively it is managing this. The state drug control authorities are in charge of providing the manufacturing licences for a medicine, and it is their responsibility to conduct periodic inspections for compliance and to renew licences after the specified number of years. In practice, manufacturing unit inspections are far behind the periodicity required. The number of inspectors deployed by states and the union does not even cover half the requirements. Nor are there any effective onsite inspection and certification processes for imported bulk drugs (active pharmaceutical ingredients) that go into the domestic manufacture. With a reasonable number of staff and testing laboratories, and with the states and the union acting together, quality checks at the point of production could easily be organised, despite the large number of manufacturing units, since manufacturing is geographically clustered. But the political will and the administrative competence to organize this have been limited.

There are even larger gaps, where currently no one can be held accountable. Neither the state nor the union need to give marketing approvals after the fi rst four years. Any trader can source the drug from any state and market it anywhere else in the country, and manufacturers can supply to these traders. Traders will, of course, tend to source from where it is most affordable. This has led to bizarre, surreal scenarios like the large poorly, regulated wholesale medicine markets, the most infamous example of these being the one at Bhagirath Palace in Delhi

There is a provision for both state and central authorities to draw samples from retail for quality testing and periodically inspect manufacturing units for compliance. Not only are drug controllers understaffed and equipped for this, but the follow up action on the already-identified spurious and substandard drugs to fi x the systemic gaps is most uncertain and unsatisfactory. A follow-up action is also complicated by the fact that some manufacturers have parallel manufacturing units for the same brand name, of which a few are USFDA-compliant and others are placed in states with weaker regulations, or manufactured through contracting arrangements in unlisted units.

Other than the vested interests that benefit from the fragmentation of accountability and weak institutional capacity to regulate, the governance failure in this domain owes a lot to the neoliberal policy discourse where India is projected as successfully moving away from the licence raj and removing constraints on the “ease of doing business,” so that huge profi ts can be made in the sector. But in the absence of effective regulations, with manufacturers trying to cut costs in a very competitive market, it will only become a race to the bottom, both for the industry and for people’s health.