Leprosy Control- Beyond the rhetoric of elimination

Conversation between Mr Antony Samy (AS), Mr Stanley Kingsley (SK),

Dr. Yogesh Jain (YJ) and T. Sundararaman (TS).

TS: Happy to have all three of you Dr Yogesh Jain (YJ), Mr Antony Samy (AS) and Mr Stanley Kingsley (SK) for this conversation. Mr Stanley Kingsley has a lifetime of work in leprosy. He is senior research executive in Bombay Leprosy Project, a NGO based in Mumbai that has special focus on leprosy research. Mr Antony, another lifetime leprosy activist is one of the founders and current Chief Executive of the NGO called ALERT-India. ALERT-India stands for Association for Leprosy Education, Rehabilitation and Treatment, India. This was founded in October 1978 and works largely in Maharashtra. It has a governing board, and its current chairperson is, our first Medical Officer- Dermatologist, Dr. Pankaj Maniyar. Yogesh, we know well. Other than his many introductions, he has addressed leprosy as a primary care physician and public health practitioner in rural Chhattisgarh for over two decades. He is also a part of the RTH Collective that publishes these conversations.

TS: Our first question. We have declared elimination of leprosy many times. But yet from most reports, including the recent Annual Report of National Leprosy Eradication Programme (NLEP) it persists. How do we understand the progress made and the meaning of elimination?

AS: If we go by the literal understanding of the term elimination, we never really eliminated leprosy. WHO defined elimination of leprosy as a prevalence of less than one case per 10,000, and this is explained as leprosy ceasing to be a public health problem. India declared leprosy eliminated in 2005, then re-declared it again in 2018, and now we have a new deadline of ‘zero leprosy’ by 2030. But despite all these declarations leprosy remains a public health problem. A prevalence of less than one per 10,000 country-wide makes little sense, since this was always an endemic disease. There are many states and within that many districts where leprosy is a major public health problem. But the bigger problem is that declaration happens without verification, without any authentic confirmation of epidemiological status, and without disaggregation for regions and communities.

SK: I begin by acknowledging that there have been significant achievements with the introduction of Multi-Drug Treatment (MDT). Because that’s very safe and effective regime. We have cured over 12 million leprosy cases in India over the earlier decades. However, the declaration of elimination remains a political statement. The evidence did not support it. Since 2008 there is no significant decline in prevalence rate (PR) or the incidence as measured by the Annual New Case Detection Rate (ANCDR). In 2024-25, 100,957 new leprosy cases were reported which is an ANCDR of 7.00 per 100,000. As of March 31, this year, 82,297 cases of leprosy were under treatment, which is a PR of 0.57 per 10,000. Of these 63 % were Multibacillary (MB). Further, 4.68% were children, and child cases exceeded 5 % of newly detected cases. All of this indicate active transmission. About 40% of cases are in women. A small proportion of children with leprosy (1.2%) had already developed permanent disability at detection. In absolute numbers that is still far too many children developing disability. Wish we have the same concern for this failure as we had for disability due to polio. Of cases at all ages, grade 2 disability rate is 1.88% and new disabilities exceed 2 per million population. 10 states and UTs report new disability rates above the national average. These are the official statistics of the National Leprosy Elimination Programme (NLEP).

Further four states—Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, Maharashtra, and Odisha—along with one Union Territory, Chandigarh, have yet to achieve a PR below 1 per 10,000. The districts having more than 5 per 10,000 population PR increased from 40 in 2023-24 to 44 in 2024-25. And 4 districts (Chandrapur and Gadchiroli in Maharashtra, Sarangarh in Chhattisgarh, and Boudh in Odisha) reported ANCDR above 50 per 100 000 population. Which is huge. So much for the rhetoric of elimination. India contributes to 60 % of leprosy cases in the world.

TS: But why was there this pressure to go for elimination, or call it elimination?

YJ: I remember being concerned about the definition of elimination in early 2000s when this issue was being discussed. The thrust for elimination was a WHO led initiative. The WHO had already decided to wind up the leprosy program at the international level, and they recommended that all countries which reach less than 1 in 10,000 prevalence of leprosy, could declare leprosy as an eliminated disease for public health purpose. Thus, the pressure was on governments to declare it eliminated. Two stratagems helped Government of India claim elimination. One was basing in on PR measurement at the country level, which obviously is nonsense because we leprosy is endemic disease with diverse prevalence across states. The second was that instead of a 1 in 10,000 prevalence, government of India used the definition of 1 in 10,000 incidences. Which was, I think, really changing the goalposts.

AS: The introduction of multidrug therapy in the 80s and the reduction in duration increased the number of people declared cured. In my understanding this is what propelled WHO to declare elimination. I asked one senior WHO officer- you have not checked, not examined the data in the field. We know that the disease persists in many hotspots. So how did you declare that it will be eliminated in the course of time? He used the word, it will “wither away”. An expectation that below a certain prevalence rate, transmission would not happen. This expectation had no basis in scientific evidence. But this statement was made on a public platform on which I was also present- at Agra. Maybe it’s true for some diseases, but for leprosy, it’s pretty false. I would also evidence this view based on our field experiences. We work in Palghar, we work in Nandurbar, Dhule, Gachiroli, Chandrapur. In all these places the incidence remains very, very high. Reported data itself shows high incidence, but if one goes by our experience, we have a lot more cases than is reported.

TS: If I hear you right, you are stating that this rhetoric of elimination was not just mistaken, it was a public health problem in itself!!

YJ_ How can a disease’s prevalence be less than of an incidence if it is a chronic illness? So, if the incidence is high, as we are seeing from many different areas, it’s a matter of concern that the disease is being declared as eliminated on a national average. What I think has happened largely with this declaration of elimination, is that we have eliminated the program, not the disease. Leprosy was one of the best examples of vertical programs, but this was hastily disbanded and handed over to the horizontal system which did not have the capacity to diagnose or to manage leprosy. Existing skill levels of both the doctors and the laboratory staff fell suddenly, missed diagnosis became more common and this compromised surveillance. After 2005, leprosy diagnosis was escalated to the district level. A district leprosy officer would have to confirm a diagnosis of leprosy, and then only the name would be entered into the medical records. Such, manoeuvres help declare lower numbers consistent with the rhetoric of disease elimination, but this is bad public health, and in the process, we undermined the program.

SK: Yes, I agree with Dr. Yogesh. Soon after achieving the elimination target, the integration of leprosy services into the frail general health care system was hurriedly announced-. without any proper post-elimination policy that was implemented or planned at that time. This went along with dismantling the medical infrastructure linked to leprosy, banning the active case-finding measures and closing skin-smear testing facilities, the last of which was one of the essential tools of leprosy diagnosis.

AS: To state that the district nucleus team will take care of these technical aspects was non-starter in terms of stated purpose. This district nucleus has never been trained. This district nucleus just put together the NMS (non-medical supervisor) and one medical officer as leprosy officer. The leprosy officer appointed is trained for five days. On what? On record keeping. Repeatedly in public platforms, we have asked what is the nature of this nucleus and what is the strength of this nucleus without which you cannot save the program. This remained in paper. The NMS are shouldering the programme. But they are a dying cadre. There is no fresh recruitment. Ten years ago, when I checked, there were 150 people NMS in Maharashtra. Now, there will not be even one per district or two per district. And mostly, they are assigned to clerical data work. So, post elimination we had a program built on vague assumptions and weak pillars.

TS: Is it possible we would have done better if set a more realistic date for elimination or should we not have any date at all? How do we design a programme without targets?

AS: Setting a date is an anomaly for a disease where you have not done a thorough investigation of the ground-level reality and then ascertained the status in different geographies, different dates. The same date for every district is not rational. It is not based on any epidemiological ground reality verification. But for that we need to get better baseline information from district surveys.

SK: Achieving the elimination target as defined is not the end of leprosy – the programme needs to address several emerging challenges of post-elimination issues which are clinical and social, besides ensuring a long-term care for about 2 million people with disabilities due to leprosy living in the country. Tackling these issues is not solely dependent on expertise, resources, and technology. It requires strong political commitment, responsive health-care system, robust surveillance and an enabling environment. So No; – better not to set a date for elimination.

TS: There is a problem in large districts and states where PR is low, but due to large population size the absolute case load is higher, such as in Uttar Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh, and these states account for a major part of disease in India, post-elimination? So how do we actually juggle around with targets in such a situation?

SK. In fact, WHO has disregarded using the term elimination since 2007. Because they realized the catastrophic effect of this in several aspects. And instead, since 2011. they encourage just stating strategies for reducing the disease burden. That should be our approach also. There is a WHO call for interruption of transmission by 2030. WHO’s 2023 definition for ‘interruption of transmission and elimination of leprosy’ notes that ‘an absence of child cases for a period of at least 5 years provides evidence of reduced transmission’, although such a criterion does not mean that transmission has fully stopped, given the long incubation period.

In the recent National Strategic Plan of the Government of India, they have set a target of attaining below PR of 1 at the district level in all districts by 2025, a milestone we have crossed, and in all blocks by 2026, and to achieve zero leprosy transmission by 2027. None of these can be achieved in any accountable manner, and measuring achievement is even more complex. It would have been better if the plan had been limited to periodic measurement of prevalence rates district-wise, monitoring change and basing district-strategies on this information rather than on any deadline for elimination. That would be more consistent with the disease dynamics of leprosy. Leprosy has a long and uncertain incubation period and disease may manifest long after infection.

AS: I think it is simpler for us to state that wherever there is new case incidence we should not accept elimination as having been achieved. And incidence of paediatric cases and high proportions of multi-bacillary disease, indicate ongoing active transmission.

TS: To move on, acknowledging that leprosy incidence is a persistent public health issue, what should be the focus of measures required to prevent transmission. Are the National Strategic Plan (NSP) strategies on case detection and treatment adequate?

AS: I would focus on three strategies to address the stagnation in leprosy control. First is to reinstate leprosy-trained cadre into the public health system. There is no cadre as of now. This could be a physiotherapist, it can be a nurse, it can be anybody from the public health system pulled out and trained specifically for leprosy- skills required for diagnosis and confirmation of leprosy and to support treatment plans. The current reliance on referral to district for confirmation fails, because most suspected persons would fail to go at an early stage of the disease and because there is a loss of skill at the district level. We need the skills at the frontline. If frontline workers fail to suspect, then it gets wrongly diagnosed or ignored.

Secondly, a confirmation network with trained cadre. This need not be by resurrecting the old paramedical cadre of Non-medical Supervisors (NMS). A more appropriate choice, suggested in national workshops is to train physiotherapists for this role at the block/district level. This would also address the problems of disability assessment and planning the management of diagnosed leprosy- as care coordinators. In coordination with medical officers, they would start the medicines required. All this is not rocket-science. If a person is qualified and trained adequately to diagnose leprosy and also assess nerve involvement and advice and give correction in the public health system, it will be wonderful.

The third thing is very important is recognize special referral service network with fixed days and time in places where it is needed. These are specific notified dedicated centres with trained medical teams for receiving referrals, oversight over treatment plans,managing complications and ensuring that patients are cured and with an appropriate follow up plan. Public and providers should also be aware of where to turn is they need to consult on leprosy.

TS: While I agree with a leprosy trained physiotherapist at the district level or even block level- since the physiotherapist is required for many roles, even when not managing leprosy. I also see the necessity of a specialised referral centre for treatment, especially when there are complications. But I am uncomfortable with this suggestion of introducing a leprosy trained cadre at the primary centre level. As case incidence is very low, they will see few cases and therefore they will continue to lose their skills. And if the person’s work is only leprosy, he/she is unemployed most of the time. And since the system does not want that, even existing leprosy staff get deployed in all sorts of supportive work. This is the problem of all disease-specific cadre. Disease specific cadre are effective when the disease incidence is very high, but as the disease incidence falls below a threshold it seldom works. In one estimate we made, even in endemic districts, only about 1 in 6,000 dermatology cases will turn out to have leprosy. I think that time has crossed for a frontline leprosy cadre as an individual single disease cadre, and I don’t see that coming back very successfully. Your comments?

YJ: The point that Mr. Antony is making is availability of specialized skills, whether that is provided by a freshly created cadre, or such skills are built into existing staff. Since we don’t have such skilled people in place, there is a lot of under-diagnosis of leprosy that is happening. My perception is that actual case detection rates must be much, much higher. I can say for sure from my experience in Chhattisgarh where we see any number of patients with 6 plus or 5 plus leprosy bacilli per high power field any day with clustering in families, children are being involved, and high proportion of multibacillary leprosy including, lepromatous leprosy and lepra reactions (ENL) coming any day. I don’t see any sort of decline in the numbers in the last say 5 years at least since I have been there. In fact, I can say that I have not seen a decline in endemic areas for 20 years in at least 2 parts of Chhattisgarh that I have information from, Bilaspur and Sarguja districts. So, I would reiterate- we need specialized skills to be available both at the clinical level and as well as the laboratory level over. We also should not undermine the presence of necessary skills in the laboratory technicians, like doing split skin smears, which is a dying art along with most microscopies in any case. The challenge in leprosy is that declining microscopy is not being compensated by any point of care test for no such tests are available for leprosy. I don’t think the gene experts of the world have included leprosy in their consideration of needs for POC innovation in diagnostic methods- a problem shared by many neglected tropical diseases.

The current guidelines do envisage a trained person at the district level for confirming diagnosis, but we need such persons at block levels and even lower in endemic districts. Or they should mobile enough to be going to PHCs on specific days. Expecting everyone to come for a confirmation of diagnosis to a district level, at least in high burden states is not feasible.

AS: The leprosy officer at the leprosy referral centre, should not be based on the current five days training. These officers should be given at least three months training, with refresher training for two, three years. Such centres being fewer would need facilitated referrals to ensure access. But referrals have to be to persons with such level of skills. We can work the out the level or numbers where they should be available, depending on the district.

SK: Sir, I would like to comment on the two aspects of the discussion so far. The NLEP have achieved functional integration with the health infrastructure and human resource at the primary level. Here we are only ensuring that the MLHP and doctors are oriented to suspecting leprosy and providing the follow up required. But the NLEP has not achieved integration at the secondary and tertiary level where we have a larger skilled manpower available who could potentially manage leprosy and leprosy related complications. The fact is that officially they have not been engaged in the NLEP activities. The dependence is on the depleting numbers of the earlier staff of the vertical programmes. It is at this level that we must build the skills required for confirmation, treatment plan, management of complications and of nerve involvement and disability. We can often use much more of available infrastructure and human resources at these levels to serve these leprosy patients. That is one point.

In terms of interruption of transmission, we need three additional strategies. First, frontline workers need to look beyond anaesthetic skin patches in active case detection for leprosy. We need to draw attention to detecting cases that present as non-anaesthetic skin patches like nodules, papules, infiltration. Such cases are important contributors to sustain the transmission but are often missed during these case finding activities. Go beyond the patch approach to the other obvious skin-signs.

The second major strategy would be community engagement. No public health program can succeed without active participation of the local community. And because leprosy is basically a public health issue, we need to engage community at the level of creating awareness and promoting voluntary reporting even for the stigma reduction strategies. This should be an official program adopted by the NLEP by engaging the community at various levels.

Third, we need to do better at the engagement of private sector in leprosy diagnosis. An unknown number of leprosy cases still seek treatment from the private health sector, especially from dermatologists. They should be required to inform and register these for treatment with the district leprosy team.

Finally, I would emphasise integration of leprosy case detection with programs like non-communicable disease (overlap on neuropathies) and NTDs (neglected tropical diseases). Leprosy is also one of the NTD. The better the attention to all skin diseases and other skin NTDs, the better the outcomes for leprosy case detection.

TS. I am happy you mention this. Reminds me of the skin case detection camps we organised during my Chhattisgarh days for active case finding of leprosy. Organisers would be disgusted if out of 5000 cases there is only one or two leprosy cases. But what of the care the rest of the 5000 required? It may be fungal disease, but the patient requires treatment. The point is if we take every skin disease seriously and try to make sure that they are adequately treated, you will pick up those which are not responding or you will notice leprosy when it is. If you just look for leprosy and the others you ignore, if you don’t take fungal infection seriously, which is very common, you will miss leprosy also. Similarly for leprosy presenting only as neuropathy which has more non-leprosy related causes. Both dermatology and peripheral neuropathy have to be addressed rather comprehensively to be able to pick up the leprosy-needle in the haystack of more common skin and nerve lesions. This is even more true in a place like Uttar Pradesh where absolute numbers of leprosy are high but prevalence rates are low.

AS: Again, the basic missing link in the argument you are making is a person trained to detect and treat skin cases. Dermatologists are an elite, very scarce cadre. There was a survey done a decade ago in Uttar Pradesh, which showed about 100+ dermatologists state-wide with almost all of them located in the city of Agra. Not anywhere else. This city-based dermatology work is a weakness. If a broad dermatologists-engagement and training take place, what you say will be worthwhile. Our focus should now be on overcoming the hesitation of a general practitioner or MBBS qualified persons to treat skin cases and to support development of their competence in this area. This is a serious limitation that needs planned solution.

I would also endorse Kingsley’s observation for greater attention to detect early signs of lepromatous, early signs of facial expression, the changes in the skin, nodules in the earlobes and this type of identification moving away from the patch, patch, patch propaganda. In our work in the endemic districts of Palghar and Dhule and in Nandurbar what we advocate now is greater observation of skin and as well as for all early signs and symptoms of infectious types of leprosy. There are other examples. In very endemic places, we even know of efforts where trained manpower moving around in the marketplace suspect and bring people whom they think are looking like lepromatous cases or with leprosy signs. 90% of them turn out to be leprosy cases. This can be done in endemic area.

And I would add to this immediately that yes, missing pure neuritic leprosy has been one of our challenges in the leprosy program; for leprosy causes a lot of disability in form of claw hands and other devastating handicaps. Even more difficult to identify if it is unilateral nerve disease but not beyond a skilled leprosy control officer.

TS. We have a large workforce of MLHPs and PHC doctors in health and wellness centres. Though skin diseases are not part of the 12 services, an oversight, many are addressing this disease too. In a few centres in Kerala, I found PHC doctors in Kerala availing telemedicine support to provide comprehensive care for skin diseases. Because it is superficial and visible, telemedicine could particularly help. And I also found that after six months, the tele-consultations are less as PHC doctor has learned to manage the cases He doesn’t need to consult so often. In tele-medicine it is not the connectivity that is the problem- it is the readiness of people at both sides of the pipeline.

TS: But moving on: what are your observations on current regime of MDR? Are we happy with our treatment regimens now? Is leprosy resistance a problem or a problem of the future? When I was co-chair on the joint monitoring mission, there were people insisting that resistance is no problem in leprosy at all. But at the same time, we had tertiary care people who were saying different. And I remember, the multi-drug therapy started because of Dapsone resistance.

SK: Broadly the current protocols of treatment and cure completion rates are alright and resistance is low. Requires 6 months treatment for pauci-bacillary cases and 12 months for multi-bacillary cases with three drugs- Dapsone, Rifampicin and Clofazamine. The recent report by WHO states a 1.3% of resistance in relapsed cases with 1.1% of cases resistant to Dapsone. NLEP 2024-25 reports, 718 relapsed cases mainly from Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, Bihar, UP and Rajasthan. But resistance as a cause of relapse, as different from re-infection is not studied. So, unlike in TB, drug resistance is a big threat.

YJ. My view might ruffle a few feathers. I want to remind ourselves that leprosy is first a mycobacterial disease, like tuberculosis, though it is a different mycobacterium; and the second that it is an immuno-inflammatory illness. It is not due to a bacterial toxin or antigen but an immune reaction to the bacteria that is causing the problems. I worry that when TB illness takes a 4-drug daily course for 6 months, how does once a month dose of Rifampicin work? I am worried that the MDT regime recommended by the WHO in 80s was probably a poor strategy for poor people. Whereas in the books of medicine and as well as in a practice of leprosy management in Latin America and in US, you get daily Rifampicin. Further we know that Dapsone is an immune pro-inflammatory drug and in fact, and my colleagues and I have seen a number of patients getting worse with it. There is a role for immunosuppressive drugs like Clofazamine to some extent, but also other immuno-suppressive drugs like we give for type 2 lepra reactions. I would urge a re-examination of the content of the current protocol which has one drug given once month, another with the main dose on one day per month and small dose thereafter and a third given daily. Further we see many people getting neurological worsening on treatment with MDT, and these would have benefitted from immunosuppressives. This is somewhat ignored in the very regimentalised way of giving therapy. In fact, raising questions about the drug efficacy is considered a crime.

AS: Let me add to what Dr Yogesh has said. In a recent international leprosy conference in Indonesia, senior dermatologists expressed very strongly that current MDT is inadequate measure, and this prescription of 12 and 24 doses is leading to the persistence of infection in the community. In their view the duration should be till the patient is relieved of the bacterial load, and not based on a fixed duration from date of first prescription. I am not a medical person but to the best of my knowledge when we began work a few decades back, 80 % of leprosy were pauci-bacillary and only 20% of the patients were multibacillary. Today, the situation is reversed. It is 50 to 70% multibacillary and 20 to 40% pauci-bacillary. Few dermatologists in tertiary care hospitals adhere to the standard MDT regimen as recommended by NLEP and they use their discretion to add other bactericidal medicines. And to include daily rifampicin. However, adding more antibiotics also risks causing leprae reactions, and frequent episodes of this leads to more never damage and disabilities unless these are well managed.

SK: I remember in 1991, WHO introduced RCT trial with daily rifampicin, rifampicin and ofloxacin for 28 days for all the multibacillary forms of leprosy which has a high bacteriological index more than 3+. They have withdrawn that regime because over 60% of those patients developed severe form of leprae reactions. Using immune-suppressive agents either in the form of steroids or in leprosy vaccines (under trial), was also found in one study to increase lepra reactions, and even using steroids as a prophylactic in combination with MDT did not reduce the incidence of reaction. This could explain the reluctance to adopt daily regimes. But I have also have found that many leprologists do continue with more than 12 months MDT in high bacillary load cases and the reduction from 24 months regime to 12 months for multi-bacillary cases was, in their view, hasty.

TS: You seem to suggest that treatment completion in multi-bacillary leprosy should be done with tertiary care consultation. And what about type 1 and type 2 lepra reactions (lepra reactions are acute, recurrent worsening of the disease due to immune changes which often present with systemic illness). Have these decreased? Do these need tertiary care?

SK: Lepra reactions remain frequent especially during post-elimination phase. NLEP (2024-25) reports 13,441 lepra reaction cases, of which 75.5% were Type 1 reactions and 24.4% were Type 2 Reaction. The DERMALEP (2017-18) survey done by dermatologists from 20 states of India reported a higher incidence of almost 30.9 % whom 57 percent had type 2 reactions and 43 percent, type 1 reaction. Management of chronic and recurrent ENL cases (same as lepra reaction type 2) with systemic dysfunctions pose a medical challenge as there are no effective anti-reaction drugs that control multiple reaction episodes and offer complete recovery and many become steroid dependent. Addressing the psychological issues and ensuring mental wellbeing is also an enigma for the clinicians. This requires composite management that is being which ensures that besides medical recovery, mental well-being also needs to be taken care of. Paradoxically our NGO run referral centre sees patients referred from all medical colleges in Mumbai for uncontrolled leprosy reactions, mostly ENL. Thalidomide helps, and we have been able to access it, but we also see thalidomide failures and need to find more effective alternatives.

TS: Just a little bit about your NGO clinic, where is it located?

KS: Bombay Leprosy Project has 5 referral centres running across Mumbai in major hospitals like JJ Hospital, Bhaba Hospital, Sion Hospital, Dharavi Urban Centre. We get referrals from primary health facilities as well as from the major medical colleges of patients who could not be managed by them, mostly lepra reactions. Our referral centres are essentially primary care facilities, but with competence in a specialised area of medical care. Such centres may be required in many endemic districts.

TS: Have we met the goals on prevention of deformity and for reconstructive surgery?

AS: Disability prevention requires identifying nerve involvement and where there is nerve involvement, addressing it with a combination of physiotherapy and counselling to prevent disability from developing. Do note, that though a person is cured of active leprosy, the nerve involvement is unlikely to reverse, and without preventive measures, disability in leprosy can begin and happen years after “cure”. Diagnosis is relatively simple- nerve palpation and confirmation of nerve involvement, and so are the physiotherapy exercises required. Every block, especially in endemic areas should have a leprosy officer, preferably with physiotherapy skills who address this. Physiotherapy-in-time almost completely eliminates the need for surgery. Unfortunately, the opposite is happening. The focus is on disability surgery with targets set for identifying number of surgeries done and these are often done with inadequate pre or post physiotherapy, leading to poor outcomes. Many surgeries could have been avoided. Disability does not equal surgery. Guidelines by ILEP agencies on who needs a surgery is very clear but not followed, which I think is a result of set-targets to which funds are linked.

SK: There is an estimated number of 2 million people living with disabilities due to present and past leprosy, and even post-elimination this pool swells year by year, because about 5% of the new cases detected every year are reported with permanent disabilities viz. grade II disabilities, and another 3 to 5 percent may develop disability during or after MDT. Monitoring nerve functions and managing neuritis during leprosy reactions effectively prevent new disabilities. The NLEP did not achieve its target to reduce the grade II disability rate by 30% from 2010 to 2015; rather disability rates increased by 26%.

The Disability Prevention and Medical Rehabilitation (DPMR) programme launched in 2007, under the NLEP, was an important milestone and major opportunity. Unfortunately, the focus of this program was selectively on providing Micro-Cellular Rubber (MCR) footwear and conducting Reconstructive Surgeries (RCS) and funds were linked only to these two activities. The more important tasks of early nerve involvement and impairment detection, treating them adequately and preventing them from developing permanent disabilities did not get enough attention. We needed to have done this by integrating wound care, disability and rehabilitation services with those that already exists in our public health system at the secondary and tertiary care level.

Even with reconstructive surgeries there are a number of challenges. During 2024-25, a total of 1,575 RCS was performed across India, with 388 (24.6%) conducted by government institutions and 1187 (75.4%) by NGOs. Most reconstructive surgeries (RCS) performed are aimed at anatomical corrective procedures of the deformity and not on functional restorative procedures. Least importance is given to preventive surgery such as nerve release and skin graft. A long-term (average 4 years post-surgery) follow up assessment of cases undergone RCS for hand deformities done at ALERT-India in rural districts of Maharashtra revealed 18% benefit of surgery cosmetically; loss or change of function (vocation) benefits in 11% and better social participation in 6% of cases. We should be doing much better.

Finally, surgery is not the end to any disability. Since sensory loss due to primary nerve damage remains lifelong, despite surgery or correction, affected persons need to take special care of their affected limbs for the rest of their life. But this awareness is grossly lacking. Many patients believe that once they have undergone surgery, they have become normal, and they tend to use their limbs like normal and this leads to further damaging their affected limbs.

AS: We were all very enthusiastic when DPMR was launched. But the programme forgot deformity prevention except for MCR footwear and concentrated on medical rehabilitation and even within that surgery. (Even with respect to MCR, both quality assurance and transparent procurement is far from achieved). A point that we made repeatedly is that when a patient is certified as cured or treatment completed it doesn’t mean that the neurological problem leading to deformity will not progress further because the nerve that is lost does not regenerate, and therefore patients require continued support and care.

YJ: I would concur with the recommendations that Mr. Antony and Mr. Kingsley have made and commend the work of their NGOs. But my larger concern is about the clinical deserts of central India where reconstructive surgery as well as any other rehabilitation services are far from the people who really require it. My charge against the NLEP that they have abandoned their commitment to these aspects of leprosy care. There are few hand surgeons or physiotherapy services in the public system. Its left to NGOs and other smaller groups to provide care for these most marginalised people, while administrative attention is focussed on elimination through statistical and publicity strategies. The problems are extensive, but remain largely invisible.

TS: Finally, your comments on leprosy colonies. Do they survive? Should they survive? I was told at last count there were 700 to 800 leprosy colonies.

SK: Unlike other countries, most leprosy colonies in India are voluntary due to stigma and discrimination and not by forced segregation. The Lepers Act of 1898, was repealed by the Indian government in 2016 following the recommendations from the Law Commission of India. However a total of 81 laws that discriminate against people affected by leprosy still exists in several states and we need to remove these. In the last few decades though the number of leprosy colonies that exists in urban and rural areas did not decrease, the number of families with affected people residing in these colonies are decreasing as a result of death due to old age and changes in land utilization patterns. To my mind, these should be phased out since such colonies perpetuate stigma and exclusion of these people. But with welfare and livelihood schemes for these existing colony inmates so that they can reintegrate into their family or society and they can live a dignified life in society. We need an inclusive approach is my humble suggestion

AS: There are about 700 colonies, but one does not know for sure. We have initiated a campaign that the youth of the colonies must be integrated, have their own organizations and be able to access welfare facilities. To a considerable extent this transformation has happened or is underway in urban leprosy colonies transformation. In Mumbai for example the colonies have transformed. There is MCR provision in the colonies and disabled patients get monetary support from the corporation. Many of the leprosy workers in our programme are youth from leprosy affected colonies. But about 50 to 80 percent of leprosy colonies are in rural areas and there these welfare measures are not reaching.

SK: I would put rural colonies at close to 80%? Some of these colonies have been adapted either by some religious trust, often church-based trust or some other philanthropic organization, including some CSRs. The majority of these colonies receive support from one major Japanese NGO called the Sasakawa Leprosy Foundation. These colonies have formed an association for people affected by leprosy, which has been recognized by WHO and Government of India and through their association, welfare schemes have been implemented in many of these colonies.

TS: Thank you all for your time. If I were to attempt a summary, I hear five main points.

- The political rhetoric of “successful” elimination of leprosy and even the public health use of elimination as a target has not been helpful. Leprosy remains a major public health challenge, and we must acknowledge and address it as such.

- The focus must be mainly on early identification of leprosy, well before deformity sets in, and this requires community engagement, private sector engagement and better clinical protocols for case detection that go beyond only patches as features to be looked for.

- There is a need for ensuring primary healthcare facilities in endemic areas and all blocks and district hospitals in most states have staff, medical and para-medical, who are specifically trained and supported for leprosy detection and management. Primary care centres where all skin diseases and all peripheral neuropathy are part of care protocols, will identify leprosy cases better than reliance on active case finding drives using occasional skin camps for leprosy as the main strategy.

- A network of referral facilities- some of which could be situated primary level, but which has the necessary clinical and laboratory skills also needs to be established. These are urgently required for confirmation of cases, for slit skin smear examinations, and for management of both lepra reactions and leprosy relapses,

- After treatment, leprosy is no longer infectious, but when peripheral neuropathy is present, it remains a life-long chronic illness. Addressing this as a chronic disease is essential to prevent disabilities and respond to them. Physiotherapists have a key role to play in this.

We hope to hear back from our readers and will direct the questions we get to the participants of this conversation, for their responses.

About the Participants:

Stanley Kingsley

Stanley Kingsley, who trained as a physiotherapist has a 38 year experience of working with leprosy. He is currently Research Executive at Bombay Leprosy Project, Mumbai, a position he has held since 2021. Earlier from 2005 to 2020 he was in charge of epidemiological monitoring and later of knowledge management in ALERT India. He had qualified as a physiotherapist from CMC Vellore in 1986 and from 1987 to 2004 worked as the physiotherapist in Bombay Leprosy project. Has worked as evaluator, trainer and consultant for a number of projects, supported by international agencies and has a number of scientific publications and papers in over 7 International Leprosy Congresses to his credit.

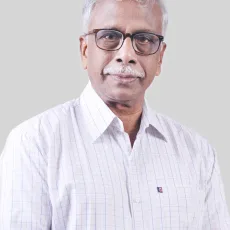

Mr. Antony Samy

Mr. Antony Samy is a professional social worker who is currently the Chief Executive Officer of ALERT India. He is working with Association for Leprosy Education Rehabilitation and Treatment – India ( ALERT -INDIA), a Mumbai based organisation for over 40 years. He has done his post-graduation in Social Welfare Administration from TISS, Mumbai.

Dr. T. Sundararaman

Dr. T. Sundararaman, His experience with leprosy is based on interventions of the State Health Resource Centre to address leprosy control programmes in the state through Mitanins and through health systems strengthening efforts in Chhattisgarh in 2002- 07 and later as co-chairperson of the Mid-Term Evaluation of the National Leprosy Programme, in 2014.

Dr Yogesh Jain

Dr. Yogesh Jain, has extensive work with leprosy in rural Chhattisgarh as a public health practitioner and a primary healthcare physician working with Jan Swasthya Sahyog, and more recently with Sangwari.