Nutrition and Growth Standards -

....Seeing Beyond the Smoke and Mirrors:

Dr Yogesh Jain (YJ), With Dr. Pavitra Mohan (PM), and Dr. Rakesh Lodha (RL).

YJ: To start with, this is such an opportunity to be having a conversation with two comrades in arms, who are scholars in their own right for the last 30 years. Pavitra Mohan and Rakesh Lodha, who are paediatricians like I have been. Pavitra, after an initial stint in academics as a paediatrician in Delhi, spent 10 years at UNICEF before getting into primary healthcare in rural Rajasthan for the last 10 plus years. And Rakesh Lodha decided to continue at the All India Institute of Medical Sciences, but he is very much interested in development and growth and other primary healthcare issues that relate to children over the years.

Today’s conversation is about growth standards and growth references, which has been an issue in the eye of the storm ever so frequently. As I remember it, in the last 20 years, with a periodicity of every five years, questions have been raised about the relevance and the content of these standards, and how and what they measure, and what those measurements should be. Last year, the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) had initiated a process to revisit the World Health Organisation’s (WHO’s) weight and height standards for children, which have been used over the last 15 years on grounds that they may not be suitable in the Indian context1. It has proposed a fresh multi-centric study to develop India-specific growth standards. This understanding has been contested. To clarify the issues and concerns with growth standards, we are having this conversation with people who have an ear to the ground, as well as are rooted in a proper scientific understanding of human growth in children.

Rakesh, if I may start with you, in the context of the current interest in this controversy, would you like to talk about what exactly are the growth standards? Are they universal? Are they unchanging? And what purpose do they serve and are supposed to serve? Do you think they are only for children, or are there growth standards and references for adults also?

RL: We need to look at growth beyond nutrition and I think that’s what society and this country is trying. The discussion is mainly about assessment of growth of children, but I think you could look at the adult heights as well. Growth standards are basically how children could be growing provided there were no constraints to growth i.e., how could a child be growing once nutritional, biological, social, and economic constraints are removed. This is aspirational and is in terms of what is their potential to grow. On the other hand, growth references are more about how children are growing in a particular timeframe or a period, given the prevalent constraints and therefore, these just describe how they are growing in the contemporary period. Their purposes are different.

Contemporary Growth references may be more immediate so that you can have a look at how an individual child from, for example, Jharkhand is vis a vis other child during that period only. Growth standards are more about what could the potential be.

Typically, growth standards are a bit higher than the contemporary growth reference, although that is not always the case. The current growth standards that are in use are from the WHO and is based on a multi-country study of both developed and developing countries; India was one of the six countries studied.2 This study highlights that when the constraints are not there, we have a common human potential and our children would be able to grow on par with all others wherever they live. Once these growth standards came out, more than 125 countries adopted them by 2011, and more countries have done so later.3

These studies were done about two decades back, therefore the issue would be whether the standards should be revised. Certainly, one would have to do a study in a similar setting, using very stringent criteria to make sure that you have children having no constraints which would adversely affect their growth. But these revisions are likely to be upwards. As an example, I would highlight that the China growth reference curves, developed a short while after the WHO growth standards came out, were based on a large cross-sectional survey, and what they found was that growth in Chinese children, at least, in the early part, were a little bit higher than the what WHO charts show.4 What this showed that already as a population, they have been doing better than what the standards were. But, surprisingly, towards adolescence there was a gap, where a child in China may be a little bit shorter than what the person would be in the United States. So, I think, there could be a context where, as compared to references, the standards wouldn’t need a revision frequently.

The determinants of growth could be more than nutritional and economic. Even health practices and the social environment would make a difference. It doesn’t have to be money (incomes) only as money doesn’t directly get translated into health status or nutritional status. We certainly could be looking at ethnic groups and try to measure growth references to compare with standards, and I think that debate could be ongoing. Broadly, if you look at the purposes, I think the growth standards serves the purpose well both for communities as well as, to a large extent, for individuals.

YJ: This is probably one of the fantastic things that one realized at the end of setting of this 2006 growth standards debates: that human growth potential is universal. I think this was great learning for people to have. Pavitra, do you think it serves any other purpose, and should it serve more purpose than it is doing now?

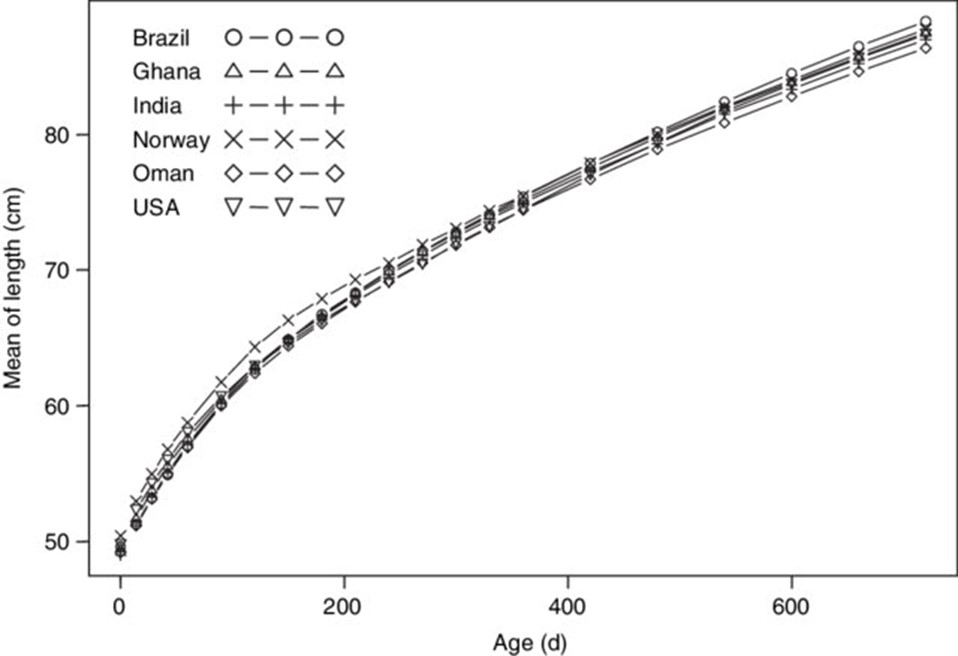

PM: Do look at this graph from the WHO growth reference study 5(figure 1), which I find to be one of the most fascinating graphs in the whole realm of child growth and development.

It shows children across the six countries – India, Norway, Brazil, Ghana, Oman, and USA – which have different cultures and different socio-economic status. If you look at the growth curves of these children for the first two years they are almost overlapping. There is a little difference between the way children grew in Delhi, Sao Paulo, or Oslo. These children were carefully selected from those who did not have any biological, social, economic or feeding practices that constrained growth. What it clearly shows is that given the right environment, all children have the potential to grow equally. One would have thought that this discussion should put to rest the question of whether children of different geographies or races have different growth potential. Whether the growth curves would remain exactly similar after twenty years is a different question. But that their growth curves would be overlapping even now is beyond doubt.

We now know that the differences that we observe between communities, between countries, and between provinces within the countries, are not because of genetic potential. The supposition that Indians are naturally smaller, lighter, and therefore we appear to have higher levels of malnutrition because we use inappropriate standards is not valid. The point is, that once you remove all the constraints, children grew equally everywhere. This is the big revelation that this study contributed to.

On your question of what purpose the study served, here is the response: it helps in understanding that children have the same potential and therefore it is the responsibility of the society, the health system, and the government to ensure that all children are able to grow in a manner that some children are capable of. As a country, as a society, or as a government we have not provided equal opportunities for everyone, and the growth standard draws our attention to this fact.

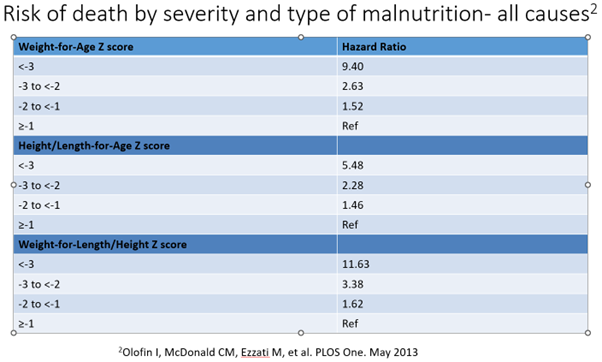

The second purpose it serves, which is more from a public health and clinical perspective, is that these curves help to define who is malnourished and who is not, which communities have higher levels of malnutrition and therefore, require more focus and resources. Figure 2 shows why it is important to use the standards to classify.

When the same standards were used across many countries, those found to be more malnourished have a significantly higher risk of death6. One of the aims of a public health program or clinical practice is to prevent death among those who are at higher risk by identifying them early and taking action. These standards do allow a clinician or a public health practitioner to identify an individual child who is at a much higher risk of death and therefore act on it. Similarly in a public health program using these standards one could identify communities with high levels of malnutrition and severe malnutrition and thereby having a high risk of child mortality. If we look at weight for height, using these curves, the risk of death increases significantly when the child is malnourished as opposed to when the child is not malnourished.

Now, there has also been an attempt to say that in India the severely malnourished children do not have similar high risk of mortality as globally or in other countries. We did an exercise several years ago and we found that almost 270,000 children in India are estimated to be dying due to severe acute malnutrition even when we use the proposed lower risk7.

To sum up, the growth standards help in determining clinical as well as public health action, and lowering these bars would mean that several children who are at very high risk of death would be mis-classified – and that, to my mind, would be a disaster.

YJ: I would add that when WHO had published this multi-country standards study, it should have removed some of the controversy about using these words “standards” and “references”, but whatever we have is what we have. Rakesh, I have a bounce back question: whether anthropometry is adequate to pick up malnutrition, to calculate the degree of malnutrition and the proportion of malnutrition? Are there other clinical tests, or bio-chemical checks to pick up micronutrient deficiencies, as opposed to anthropometry which is simple and has been used in growth standards as the WHO recommends?

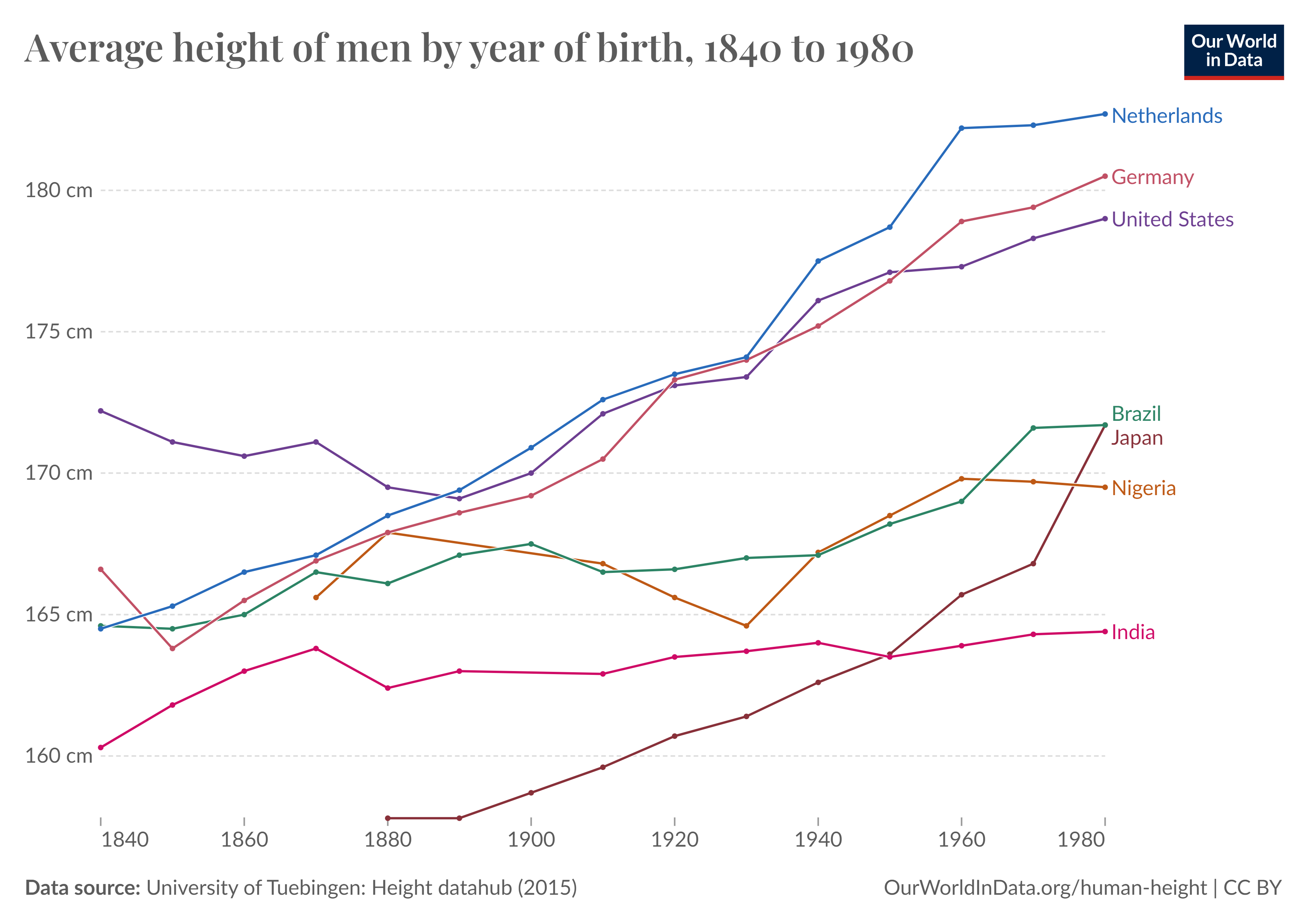

RL: It is interesting to look at the growth of people across the world. If you look at a particular country, over a year, decades, or centuries, you will broadly see that the genetics are the same. There might be some immigration, but broadly the genetic structure remains the same. This graph here from the ‘World in Data’ website8 shows data of about a century of human heights, and you can see that consistently all across the world people have grown.

If you look at the Netherlands, you can see that over about a century back the average heights of men were close to 170 cm, and today they are over 180 cm, which means it took them about a century to gain about 12 or 13 cm (4-5 inch). So, if you have adequate nutrition and the constraints are not there and overall people are doing well, it roughly takes about a century for about 5-7% increase in the height. Obviously, it would plateau off at some point, but certainly that potential is there. Now, if you look at the Indian heights currently, overall, there is not much gain. If you look at overall development, adults are at an average taller, than what their previous generations were, which can be like controlling for genetics or ethnicity. But as per the data, the gain in adult heights over the same period has been substantially less at about 3 cm.

Back to the question about whether we should do away with the anthropometry and get back to micronutrient assays and biochemicals, I think, consistently there would be data which says that the latter don’t really perform. There are too many influences on them for these two to be used as growth markers or for saying a person is malnourished. I don’t see a reason to move away from weights and heights. The data that shows the risk of mortality, which is a hard outcome, increase with the severity of malnutrition: for weight-for-height that are less than 1 or 2 z scores, the hazards of death are many fold, and 11 times for less than -3 z. We aren’t even talking about other comorbidities, or the risk of dying subsequently. These are established evidence.

Does it make a difference for an individual? For an individual, it is not looking at anthropometry alone to decide whether a child is normal or not normal. All that has been said is, a child or an individual who is below -2 standard deviations from the central value has a greater likelihood of having an abnormality. It’s not that every child that has been diagnosed as short, based on this would get on to an extensive evaluation of hormonal or endocrine disorders. But this would be one of the objective parameters that clinicians are going to look at to decide whether the child is having an abnormality. To decide whether the child needs to have a workup or an intervention. Often there is a concern that when you use these standards you are likely to have more referrals. But that is welcome and that’s how a program should be functioning where you try and make sure that you don’t miss out on people who maybe having an abnormality. When we come to the weight-for-height or the wasting component, that is associated with a proximate risk of higher mortality, certainly, one is using a more sensitive parameter even if we lose out a bit on specificity. I think that is how it should be working.

YJ: Pavitra, could you talk about other determinants of growth besides nutrition?

PM: I would like to draw the attention towards the issue of equity. Rakesh referred to the graphs which are countrywide, which gave a sweeping picture of an entire country. However, countries with higher levels of inequity are less likely to have overall gains in growth and development.

In India, one reason for suboptimal growth of children is that women’s heights continue to be much lower than comparators, even those in Africa. That brings us to the other issue, the status of women in general and their nutrition status in particular, which determines the birth weights of their children. I do not know if there is a reasonably authentic data on birth weights across the country. Whatever data we have both at the macro level as well as micro level, like the areas where we run our primary health services, shows that low birth weight proportions continue to be 25 to 40 percent across the states. I have not seen any community based study, where it has been lesser. In China, the country that Rakesh referred to, low birth weight rates are about 5%! Our low birth weight rates continue to be between 25-40% despite our annual economic growth being at 5 percent or higher. That has to do a lot with the status of women among many other factors, especially nutritional status of women. A significant piece by Dr Ramalingaswamy and Dr John Rohde brought out in late nineties, titled “Malnutrition: A South Asian Enigma”, argued that the enigma of high economic growth, yet high malnutrition levels in South Asia are on account of poor status of women in the sub-continent. This effect is partly explained by the impact of their poor nutritional status on birth-weights, and partly by inability of mothers with limited autonomy and time and skills to take care of their children.

The sheer shortage of nutritious food across the socio-economic spectrum is huge, and it is increasing in rural areas. This was seen in the data from in what used to be the NNMB (National Nutritional Monitoring Board), which has unfortunately been closed down in 2014. Over 20 years the availability and the consumption of food at the household level has been progressively decreasing. The calorie, the protein intake, etc, had been decreasing in rural India across the eight states that NNMB surveyed over decades.9

In India, malnutrition is across the socio-economic spectrum, but there are huge differentials in malnutrition levels with much worse levels in the poor economic status. When there is food shortage, there is deficiency of all the micronutrients. Unless there is a special effort like what we did with universal vitamin A supplementation, so that even if you are starving you still may not have vitamin A deficiency because you have been given high doses of it every six months. But, otherwise, when there is no food there will be deficiency of macronutrients as well as micronutrients and of course, measuring nutrition status by anthropometry will be a good way of also identifying micronutrient deficiency. If you look at the correlation between anaemia levels and nutrition levels, they are pretty much overlapping.

YJ: Pavitra has brought up this idea of equity. Height has been considered in literature as a marker of equity or adult height as a single indicator of the social capital of a society. It is a summary indicator. Heights, in that sense, have an archaeological value of society’s developmental record. There are clear differentials in the height medians among different social categories in India and differentials in the increase of height in different social categories over the last decades. The upper middle class, or the people from the general caste category, have had major increases in heights over the last few decades whereas, height increases among Adivasi women have really stalled. I want to ask you a little more difficult question now, we know that we have an unequal world in India and globally, and there are varying levels of social support and poverty levels. Despite this would you very categorically say, that there should be universal standards for human beings everywhere? Is there merit in the concerns of people about lowering the bars? Or should we doubt universal standards?

RL: When we are looking at growth from a society or a country level, what everybody would be interested in is, Could children grow better? Now that would be dependent on where you want to be. If you lower the bar, for whatever reason, and say this is how we are and this is where we are going to be then obviously, we may not be doing much. And again, one has to have a holistic view. It’s not just about the income or the food availability, it is about the social-cultural practices in terms of what we feed our children and nurture them. We now recognize in our programs that the first 1000 days are the period which results in substantial and lasting impact on the growth, particularly the height. Weight gains could happen thereafter but if somebody remains small in the first two years, it’s going to be extremely difficult to have catch up growth. With food intervention in later period , we could end up with getting kids with higher BMI and maybe more body fat, which may not be useful. The key thing is the first 1000-day period is what would be important. And that’s where I guess, that concept of appropriate feeding comes, it’s not just the amount, but also having the right variety of foods and ingredients getting into a child. As the NFHS data shows that even amongst the top two quintiles, the percentage child malnutrition is around 15%10 and I think that kind of gives us some insight into how apart from the social-economic status, the feeding practices are also what is important. This highlights the difficulties in implementation, where appropriate action is required at the individual level, and a community level, and so on. The questions should keep in focus, what’s best for children. And forget about the statistics for the time being, and say what’s best for children, right?

The statistics may not look good today, but if we accept this as normal, it’s always going to look similar. It’s not going to change. People could be comfortable with saying that, okay, we are small, we have low weights, we have low birth weights, we need less food, and so on. And the cycle would go on, and unless it is accepted as a challenge, the changes are going to happen only over many generations. On the other hand, if we have girls growing better, taller, having appropriate weight, and the next generation, possibly, will see better birth weights. And if you have to do that, you would have to use a standard where you aspire to be, over a period of time, rather than what we are doing right now.

Prasad et al11 have reported that “countries such as Vietnam and Bangladesh, which have lower per capita incomes than India have had an impressive record in reducing child stunting rates. Compared with India’s modest annual average rate of stunting reduction (0.39%), Indonesia (0.64%), Bangladesh (1.17%) and Vietnam (1.22%) recorded steep declines during the period 1995–2021”.

I don’t have data to specify it, but I think I’m just speaking of the horizon over which you need to look at how we could grow, rather than just worrying about how we are growing right now.

YJ: Pavitra, would you like to paraphrase, this assertion in your own way and then I’ll come up with another question for you.

PM: Thanks, Rakesh for bringing back this debate away from statistics to say what is required for children to grow well. And what is happening today and where do we want to go? I can say, from our own experience of running daycare centres for children under 3 years of age, just providing a nurturing environment besides food, and a safe space where there is some stimulation and education, together transforms children! They not only improve their anthropometry but it shows in the gleam of their eyes, in the pride on their parent’s faces, and in their school performance. We only measure anthropometry because that’s easier to do. But if we measure cognition and school performance, etc, there is evidence that the right nurturing environment is as important. This is irrespective of socioeconomic status, but the constraints are, of course, much more in the poorer families, etc, where the claims on time are many and the food is also scarce. But even if the food was not to be a constraint, then also the environment in which children are growing is so important-, require stimulation, love and compassion, etc. And all children deserve it! There’s no civilized society that would say that some children should deserve it more and others less.

A question may be that, within the available resources, how do you ensure that it reaches all the children? There is a published trial, the Women and Infants Integrated Interventions for Growth Study (WINGS) trial, where everything that was possible from conception onwards for the mother and then for the children, for the first two years was ensured. This ranged from ensuring sanitation to giving food to antenatal care mothers to treating every small little infection and every little deviation from the normal during pregnancy, and then safe childbirth, then, food for children and supervision and stimulation and all of that happened for two years. There was a significant increase in the linear growth of children at two years of age.12 This showed that it can be done. But this was in a highly resource-intensive and research setting. Whether making such resources available are feasible or not and how to make them available is a different question. The point is, it can be done if all the constraints were removed and all the possible care could be given to mothers. And we are not even talking of the constraints while growing up.

YJ: All three of us sort of agree that standards, even though they are aspirational, should be our benchmark by which we should be planning our initiatives, which are food and beyond food. This is a stand that all of us have been taking for years now. So, Pavitra, could you list out what are the issues that are being raised to question these standards by people now?.

PM: I think one argument, which to some extent is fine, is that these standards are over 20 years old. And, therefore, we need new standards, which is fair.

YJ: But immediately my response to that point is the standard will only go up, they cannot come down. Can they?

PM: Absolutely and I have no doubt that they will again be overlapping. For sure. Just saying that this has been used as one counterpoint.

Second, the explicit argument, is that Indian children grow differently, and therefore comparing them to the best possible scenario would be increasing the estimated levels of malnutrition, thereby also misdirecting expenditures and investments in treating children or managing the whole area of nutrition. I think this whole idea that India has been spending a lot on nutrition is an objectionable kind of argument. India’s a country with the lowest levels of investments in health and nutrition in general. Agreed??

The other rationale is fear of and a link being made about the growing obesity. A fear that, if based on wrong standards, we feed children too much, then that could lead to obesity. That’s kind of a concern. The fourth, factor which is often not obviously stated but implicit, is that there is a sense of pride. There is an explicit argument made by some economists in published papers that if India has grown economically, then how could the malnutrition levels stay so high?13 It is because we are using the wrong standards, they argue. This is a very flawed argument because even to prove that argument, what one needed to do was to use these references to historical data, and then say whether the levels are decreasing or remaining static?

You can’t use the earlier standards to measure past levels and then the current references to the current data and say that the levels have become now half of what the country is saying., The argument goes that 40% of children are currently stunted, but if you use these new references, the levels of stunting actually become 20 percent. But the point is, that you can say nothing about the trend using cross-sectional data. One needs to compare it with historical data which is also projected on these new reference standards. If you use that, the graph will remain the same as what Rakesh showed about the heights over 100 years. Using those standards for historical data and using current references for current data to show a historical trend is a flawed argument.

YJ: Rakesh would you like to add to this list or litany?

RL: I would agree with what Pavitra mentioned.

One, when you’re talking about growth and development, it’s much beyond food alone. Food is critical, both quantity and quality and the mix, and I guess the early infant and young child feeding practices too. It is a no-brainer that there should be food security. If you specifically want to address the issue about growth, then you also need a nurturing environment and it comes in different ways in terms of what environments they are in at home, and what environments they’re in the society. That’s quite a bit of an ask if one would say that, to try and modify that, but at least at an individual level one could address the nutritional practices, and to an extent bring emphasis on a nurturing environment within the household setting. And because that’s primarily where a lot of the early childhood is going to happen. Once you’re out in the world, the control over many things is a little bit more difficult, but many things could be addressed at a home setting.

The observation has been that “we have been doing the ICDS intervention for such a long time, and yet there is no change.”. Now that could have two interpretations. One, which we make is that what we are doing is not enough. Another that is being suggested is that since nothing is changing, this means that this is what the growth should be, and this is what they are, and that’s the end of it; which means that the standards that we are using are inappropriate.

We need to appreciate that ICDS needs to address the first 1000 days more effectively and it needs to go beyond nutrition. There are many studies that highlight that whatever food supplement is being provided may not really act as a supplement; it’s primarily acting as a replacement. And that is another very simple, straightforward explanation. So, I think we need a multi-dimensional inference. The current debate, reminded me of what we discussed about 11 years back, that if India is doing so well in economic growth, how is it possible that our nutritional status is worse than Sub-Saharan Africa, which socioeconomically is lower than us in many parameters. But I think when we teased out the data, and looked at almost everything, including anaemia, including infant feeding practices and many other factors, we did find that on those counts, whatever the reasons they were doing better than what we were doing.14 It is surprising to see the same arguments being put forward again!

One has to appreciate that the changes are going to take decades. If the economy does well for a decade, it does not follow that low birth weight rates, are going to dramatically drop within a decade. And again, the economic indicators are summary figures. What it hides is the equity part and whether all sections of the population have had a similar increase.

YJ: Pavitra, what do you think is the purpose of these periodic health and nutrition surveys like NFHS? And from what it shows, how do you think our child nutrition has been doing over the last three decades, particularly if you apply the equity lens on gender, social category and region, how are we faring with regards to child nutrition?

PM: These are the only surveys that tell us what is happening to children’s growth and development over years. We have, unfortunately, very little else to fall back on. The National Nutrition Monitoring Bureau was an excellent kind of a tool and a platform where we were not only looking at the growth and development but also simultaneously food availability, as well as food consumption among children and that would also tell us a lot about the quality of food and about the micronutrient intake, etc, but it was stopped a while ago. Absence of that has made a huge kind of gap in our access to information and data for making decisions and understanding what’s happening.

The NFHS surveys are absolutely important for us to know what’s happening to the growth and development of children in the absence of other state-specific or community-specific data. These large national services do provide state-level estimates, but they still miss the nuances within the state, among the different communities, among the marginalized communities, etc, where you need more in-depth understanding. But at the same time, they are the only tools we have to provide long-term secular trends. There are, of course, differences in sampling sizes, in definitions, in the age groups studied and in ways of estimating it. Broadly, what the secular trends do show is that the decline in malnutrition has been highly inadequate. There has been a decline in the levels of stunting, in levels of underweight, but very little in terms of wasting, and in severe wasting, barring certain states, where there has been up and down a bit. There has been a decline, which must be acknowledged, but the decline has been much less than what we are capable of, and what other countries have shown. The decline is probably about half of what can be potentially achieved every year. And in some parameters, like the levels of wasting, etc, it has been largely stagnant. In terms of equity, broadly, the inequity remains, and even in the top 40% of the sampled population, we still have unexplainably higher levels of undernutrition among children. And in the top 20 percent there is a secular trend of increasing obesity, which was not there 20 years ago. So that has started creeping in, and that’s again, to do, probably, with the quality of food and overall environment.

On the issue of food, other than inadequacy of food, there is also the increasing problem with regard to poor quality of food. Food which is unhealthy is cheaper, and that, again has to do with public policies. We have better access to grains, for example, but not to foods which have micronutrients or proteins. There is a need to shift from a food security to a nutrition security kind of a paradigm.

In terms of food, nutritious food is becoming more and more expensive the world over, and is becoming out of bound for a large proportion of the population. This is happening in India as well.

YJ: What are your thoughts on the problem of overweight or obesity in children? That seems to be one of the concerns that some of those who are asking us to lower the bar are also raising.

RL: Over a period of time, certainly, there has been an increase in the overweight and the obese. And again, using different references or different standards, there may be a few percentage points difference in obesity levels. It may be good to segregate the data to understand this. Typically, when we talk about obesity, most of the data would come from school-going children., This implies children who are beyond five years of age. And that’s where a lot of these other influences about the type of diet and food that they’re getting and the excess becomes important. And also in that context, the importance of physical activity is critical, and to an extent that is dependent on where one is growing up and what kind of access one has to, you know, the structured activities, be it in school or outside of school.

On the other hand, if you want to focus more on the stunting part, then one would have to be looking at that early childhood which is more critical, and in that period the concerns about overweight and obesity wouldn’t be as much as it would be in the school going age group.

One would need to do a little bit better analysis and try and develop solutions. Just saying that if population is undernourished, more food is the answer and this would mean some children would get excess is too simplistic and misleading. We need a more nuanced kind of an approach so that when we say food, we are specifically talking about and in different age groups and settings and what kind of package we deliver to make sure that children are better off.

A high sugar and a high carb diet which is not balanced would often come out to be cheaper than the nutritious or healthy diet, and that, unfortunately, is becoming a norm. There doesn’t seem to be a regulation on this, and that would be a contributor, not just to the overweight/obesity, but many other non-communicable diseases as well.

We should be concerned about obesity and overweight, but not to trade it off with accepting higher levels of under nutrition. That does not make sense at all. These are two ends of the spectrum, and one would need to understand it in as such and handle these separately.

When we talk about the constraints to growth, WASH (Water, Sanitation & Hygiene) interventions are also critical. There are enough data to support the benefits that having safe drinking water, appropriate sanitation and hygiene make to health and growth. Unfortunately, it’s not seeing that kind of attention which it should have.

YJ: I have only a couple of questions left. Just as with growth standards, there are requests for lowering the bar for defining anaemia in Indians. On the argument that we have lesser muscle mass and therefore our requirement for hemoglobin are also lower. Is this justified? And if not, how will you counter this proposition?

PM: The same principles apply. We should not be defining cut offs based on the current haemoglobin levels of India’s children or women or men. Cut-offs should be based on what are possible levels in a population which does not have any of the constraints, either in access to required nutrition or other haemoglobinopathies. High levels of anaemia seen has a clear correlation with many of the known factors: biological like hemoglobinopathies, nutritional like deficiencies of iron and other micronutrients, intestinal worms – all of which are common.

So if there are obvious reasons why women are anaemic, and if there is reasonable evidence that beyond a certain cut-off, there is a higher risk and there is a decreased oxygen carrying capacity, and there are physical impacts in terms of fatigability or in terms of poor pregnancy outcomes, then I don’t see any justification, for recommending a lower cut-off.

YJ: Rakesh, what is your take on this?

RL: When you look at these cut-offs, one may use a statistical approach and try and identify a healthy population and define as those below a certain percentile as anemic. The question is whether we take steps to address this, and try to understand why current interventions have not been effective or declare that Indians are destined to have low muscle mass, high fat composition and therefore, this is okay for us. The issue is that if you want to define being healthy, and you want to go further and say that we just don’t want people to be with low muscle mass or high fat and we need people to have good haemoglobin and good iron stores and so on. That means to me that, again, seems to be counterintuitive.

Studies clearly show the associations between anaemia and muscle mass, and this affects their lives, for example in the capacity of a person to do physical work. It may not be a dramatic kind of association, but there are associations between anaemia and muscle mass. Now to argue that you have a lower muscle mass, and therefore its acceptable for you have low haemoglobin is flawed. And why not the other way around… you have lower haemoglobin and therefore you have a lower muscle mass. The only catch is that some of these data come from studies where they’ve tried to control for, or at least define ‘Healthy” by looking at certain parameters like iron stores. If you really get down into the details one may have some debates about how you would want to do the study again. But if you look at the overall context, I don’t see a reason for lowering the standards. And again, what you do to an individual is entirely different to what to do as a community. That means if some individual comes to you with a haemoglobin of 10 you’re certainly going to investigate him/her as to why that haemoglobin is low. And if at the end of everything, you find things are fine, it’s okay, but that child is definitely at a greater risk of having or the greater likelihood of having an abnormality to explain why the haemoglobin is low, as compared to somebody who has a haemoglobin of 11. I think the entire approach, often mixes up the relevance of the standard to individual’s clinical assessment with the use of the same to measure population health with regard to implications for action.

YJ: Absolutely.

PM: I’d like to add something here. You know, several years ago, we did a review to look at childhood anaemia and find out what we know about it. And this question of, if you have been giving iron in this program for such a long time, why does it not improve? So what we found was that we know very little about the causes of anaemia in women and children at the moment. I mean, there are studies which look at iron deficiency and estimated the burden of iron deficiency. There is another study that does B12, and this third study looks only at hemoglobinopathy or sickle cell anaemia. But to the best of my ability to review, very few studies in India and that too, in different communities, that if there are 100 children or 100 women, what is that pie? What is the contribution to high deficiency? What is that contribution of or overlapping with B12 deficiency? And then it is so context-specific, there is malaria in several areas that contributes. How does that all add up? We have limited information to actually act on but we know that, of course, iron deficiency is huge and we begin there.

YJ: The Comprehensive National Nutrition survey, 2018 did try to address those, but not adequately. And even that has been misinterpreted later. In science, one of the basic tenets is to question, but certainly not to question science itself. At this moment, there is an attempt to even question science because of certain other reasons that are not science-based, and that worries me. Now I’d like to pose this last question to both of you. With all these points that are being raised about growth standards, and haemoglobin standards, and given the doubts raised about strategies, should we be bothered about these standards at all, or will it distort policy and implementation? And I want your take home message in this final answer if you can.

PM: My takeaway would be that, if we want to understand better the current patterns of under-nutrition it’s a different question altogether. There’s no harm in understanding how children are growing in one state or in one community and if the reference curves released are an attempt to understand how children are growing in India, that’s fine. But I think, trying to explain away the levels of malnutrition by saying that the high levels can be justified because we have different references/standards, is a misdirected one. It will direct away the efforts that are needed to address a serious problem. Even if you use the references that are being proposed, still the levels of malnutrition are pretty high. And to say that that is justified, and therefore it’s fine, I think, is a wrong one, and that is something that must be countered. We need to sit together and say that, okay, what we have done to address malnutrition has not worked adequately so far, but what can we do differently, and what can we do better? This discussion between references and standards and trying to explain away the high levels of malnutrition because we have been unable to address it may take away our attention and undermine the seriousness of the matter. And it’s dangerous because this under-estimation would be not only at the policy or scientific level, it could also reduce the demand for better nutrition services with lay people.

RL: While the association between wasting and mortality, a hard outcome, is well known, we also need to factor in the impact on neurodevelopment. And it’s not uncommon for people to cite the exceptions to say that, look, this gentleman/ lady is so short, but (s)he’s a genius. That doesn’t mean anything practically. It’s easy for people to cite exceptions to prove their point, but I think one needs to look at the bigger picture to be able to say that, okay, as a population, how are we doing? How is it affecting neurodevelopment on a country-wide scale- and the numbers would be large. I think these nutrition challenges need to be addressed, not just from the survival perspective, but also, I think, importantly, from the neurodevelopmental perspective, as a generation that’s going to come- you owe it to that generation. Let’s put it that way.

Reference List

2. World Health Organization. (2006). Multicentre Growth Reference Study Group: WHO Child growth standards based on length/height, weight and age. Acta Paediatr Suppl, 450, 76-85.

5. WHO Multicentre Growth Reference Study (MGRS)

8. Our World in Data. Human Height.

9. Mohan P (2016). In rural India, less to eat than 40 years ago.Times of India.

13. Panagariya, A. (2013). Does India really suffer from worse child malnutrition than sub-Saharan Africa?. Economic and Political Weekly, 98-111.

14. Lodha, R., Jain, Y., & Sathyamala, C. (2013). Reality of higher malnutrition among Indian children. Economic and Political Weekly, 48(34), 70-73.

Acknowledgements: To Ms Roubitha David and Dr Senthil Ganesh for the transcription.

About the Participants:

Dr. Pavitra Mohan, did his MD Paediatrics and worked as resident at Safdarjung Hospital, New Delhi, and then a Masters in Public Health from Chapel Hill, North Carolina and then worked for nine years in UNICEF before co-starting the Basic HealthCare Services (BHS) a not-for-profit organization, registered as a Trust in the year 2012. BHS is driven by the vision of a responsive and effective healthcare ecosystem that is rooted in the community, where the most vulnerable communities can actively access high-quality, low-cost health services with dignity. He continues to work with BHS in developing primary healthcare strategies and as a provider of rural primary healthcare in Udaipur, Rajasthan.

Dr. Rakesh Lodha did his MD Pediatrics and senior residency from AIIMS, New Delhi; has been a Faculty in the Department of Pediatrics, AIIMS, New Delhi since 2000. He is in-charge of the Pediatric ICU and also manages childhood respiratory diseases and infectious diseases including TB and HIV in children. He has been interested in the study of growth in children.

It was little lengthy, but so informative and provocative.

Regards,

An excellent conversation, covered most of the crucial issues.

Just a couple of suggestions, comments:

1. While Norway and similar data from Europe points out substantial growth in average adult heights over a century, we don’t have it – even half a century to presume. It is considered a generational growth, at least it should be collated so that the next generation is comparing it! Secondly, growth data about children which survived due to active intervention can indicate stunting as residual effect.

2. Obesity in children : Increase in Weight for age with less in height for age is expected on obesity particularly if it’s fat mass rather than muscle mass increase. How do we carefully promote protein – fat – calories consumption is still a fuzzy understanding. We do promote high protein diet but there is no clear recommendations for what a child should eat for height growth.

3. Anemia IS an enigma, around 60% are iron deficiency anemia, other micronutrient deficiencies particularly of Vit B12 needs to be studied. Again food consumption proportion and patterns still show that proportion of non vegetarian consumption and IDA don’t match.