Global Plan to End TB, 2023-2030 – How Feasible? How Desirable?

There has been very limited comments on the media and even in academic journals on the major changes in the strategies of tuberculosis, globally and at the national level.

At the Global level a High-Level meeting of the United Nations General Assembly on the End TB Strategy was held in September 2023. In the same week there were similar high-level meetings on pandemic preparedness and on Universal Health Coverage (UHC) – and these got more attention. The meeting on Tuberculosis has adopted the “ Political Declaration on the High-Level Meeting on the Fight Against Tuberculosis” (1)(UNGA,2023)

The declaration on tuberculosis is a welcome international call for ending the TB epidemic by 2035. This is a reiteration of the call that was first adopted by the UN in 2018. In public discourse this is often expressed as eliminating the disease as a public health problem by 2030, or as making the country or the world TB free. A more precise definition of the goal would be achieving the SDG 2030 targets for TB, followed by WHO End TB targets by 2035 globally, and that means achieving an annual TB incidence of <10 per lac population. Achieving this increases chances of eliminating TB by 2050. The SDG 2030 target is a 90 percent reduction in the incidence of all active disease in adults, children and drug resistant cases and a 90 percent decline in the number of people who die from TB annually by 2027, compared to 2015. It also aims for achieving preventive treatment of 90 percent of all latent TB, and all active cases being diagnosed with molecular diagnostics as compared to sputum microscopy and X-rays and treated with the latest recommendation in drug regimens. Further all, 100 percent of tuberculosis patients would be protected from financial hardship due to TB care.

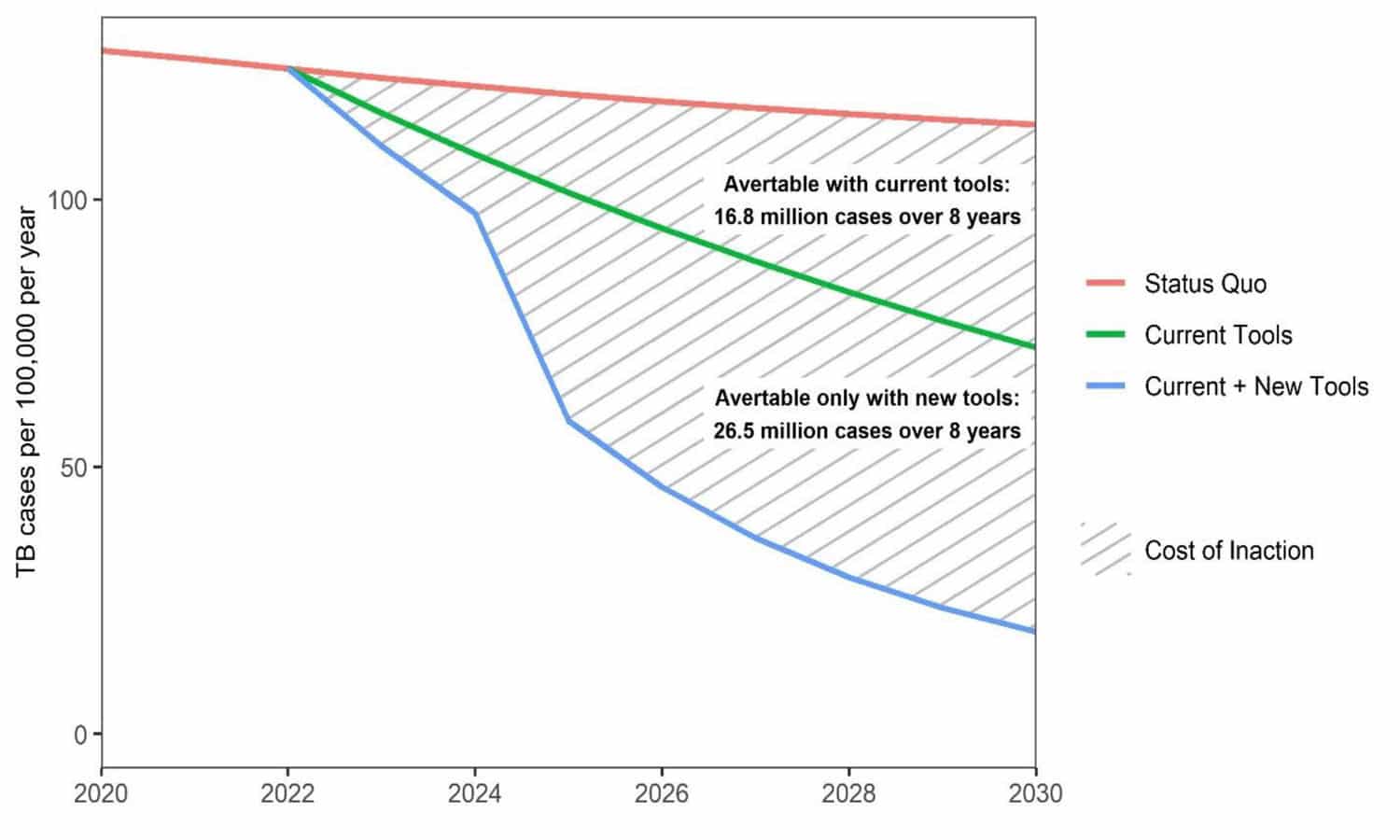

This deadline is based on two assumptions. Firstly, that there would be better deployment of current strategies, and the second assumption being that by 2025 a set of new tools or technologies would become available. In this projection better implementation using only currently available technologies would mean that the objective would be reached only beyond 2050. (see figure below) (2)(Stop TB Partnership, 2022)

Source: The Global Plan to End TB 2023-2030; Stop TB Partnership; Geneva, 2022

But five years after the end TB strategy was announced, as the Political Declaration itself expresses, the world is not on course to achieve this target. “Between 2015 and 2021, the net reductions in TB incidence and death were 10 per cent and 5.9 per cent, respectively, only one-fifth and one-tenth of the way to the 2025 milestone of WHO’s End TB Strategy.”( SDGs 2023 Special Report), : There was even a period of two years in this decade that are marked by an actual increase in both the incidence of the disease and in deaths, reversing a two-decade long trend of slow decline.

The declaration states (para 7) the deep concern that 30 years since the World Health Organization declared tuberculosis a global emergency, “the global tuberculosis epidemic still is a critical challenge in all regions and affects every country of the world, and that although tuberculosis is preventable and curable, an estimated 10.6 million people, fell ill with tuberculosis, of whom 56.5 per cent were men, 32.5 per cent women and 11 per cent children and approximately 1.6 million people died from the disease in 2021, including approximately 187,000 people with HIV, making tuberculosis one of the leading causes of death worldwide, that 30 high Tuberculosis burden countries accounted for 87 per cent of those affected, and that one quarter of the world’s population is estimated to have been infected with the bacterium that causes the disease.” Further it admits that in 2021 only 61 per cent of people with tuberculosis including 38 percent of children were diagnosed and treated for tuberculosis, that only 38 per cent of people with tuberculosis are diagnosed with WHO-recommended rapid molecular diagnostics, and only 42 percent of population who were due for treatment of latent TB received that and that about 50% of those under treatment with TB faced financial hardship due to the costs of healthcare.”

The Political Declaration also expresses concern that of drug resistant TB, “only one in three accessed treatment in 2021 and of these, 40 per cent had poor health outcomes for reasons including gaps in access to WHO-recommended diagnostic tests and treatment, inefficient service delivery models, medication side-effects, lack of access to treatment support, comprehensive social protection and care and acknowledge lack of attention and care to the needs of tuberculosis survivors for post-treatment follow-up, particularly drug-resistant tuberculosis survivors.”

It is worth asking whether given this poor performance, whether it is merely a problem of inadequate political attention and resources or whether we need to also re-think the feasibility and desirability of the current approach and it’s time-schedules. One key issue that most commentaries are seized of is global funding gap for TB. Through it has more deaths than HIV and malaria combined, it does not receive that much attention. As per WHO 2023 report, US$ 13 billion is required annually for TB diagnosis, treatment and prevention services. Only US$ 5.8 billion was available in 2022, similar to the level of 2020 and 2021 but down from US$ 6.5 billion in 2019.

In a statement issued by Peoples Health Movements on the UN Declaration, some of the other concerns were flagged.

Pressures for under-reporting incidence: One problem with enforcing achievement of targets without the material basis for achieving them, is that health workers and mid-level managers get persuaded to report falsely on program performance. The widespread prevalence of this disease is already made less visible by stigma and lack of knowledge- and under-reporting adds to this problem.

Implication that actions on social determinants is desirable, not essential. Tuberculosis is well known to be a disease closely associated with inequality and poverty. Poverty acts in many ways- the most important of which is hunger and under-nutrition. But it also acts through living and working conditions where there is over-crowding and poor ventilation and high levels of pollution. With no end to these problems in sight, it is clear that the strategy envisaged is one where a set of technological interventions delivered by the public health services can end the TB epidemic even in the absence of a socio-economic development and attention to social determinants.

Interpretation of the Covid 19 response: The optimism that such targets would be achieved stems a lot from the particular reading of the covid 19 pandemic response. In this reading, the global healthcare systems responded to the pandemic by a huge increase in investment in innovation and development leading to development and deployment of vaccines on scale within just about 18 months. In diagnostics too there was a huge scaling up of access to the rapid molecular testing for the virus within less than six months. Could this not be replicated for tuberculosis. A more sceptical view would have questioned whether the control of the pandemic was a consequence of these technologies, or only partially related to it. But the policy discourse was that if a similar political and scientific effort was launched for tuberculosis, achieving the targets which otherwise could take beyond 2050 could be accelerated to 2027.

Techno-optimism: This is a whole new level of techno-optimism- to adopt a program of action on disease control based on the deployment of yet to be innovated technologies. The key technology would be like in covid 19, the tuberculosis vaccine. But a whole new range of diagnostics and drugs would also be counted upon if funding for R&D in tuberculosis technologies was increased. Will this come to pass? We cannot rule it out- but it may have made more sense to declare the policy timelines after a vaccine was approved, rather than in anticipation of it. As of now we do have a promising six-month regime for drug resistant tuberculosis (BPalM) but a vaccine is still work in progress.

What about the scenario of progress with current tools, but better implementation.

Universalising Molecular testing: One of the new strategies is to shift diagnosis to molecular testing- NAAT (Nucleic Acid Amplification Tests). No doubt this has a higher diagnostic accuracy and could therefore reduce missing the disease in those testing negative on sputum microscopy. However, most of the transmission is from sputum positive cases. Further for most countries while the changeover to molecular testing could be achieved in more developed regions and urban centres, it would be a challenge to establish this in geographies where resources are low and laboratories poorly established. The assumption is that the finances for such expansion and the human resources required would become available. Another aspect of the new strategy is to establish molecular testing for INH and rifampicin resistance in all cases of active tuberculosis- a welcome strategy, but a challenge to take to scale for most LMICs.

Preventive Treatment for Tuberculosis (PTT)– this term refers to the identifying and treating latent tuberculosis infection (LTBI) referring to infected persons without active disease. This is a significantly new development. The earlier wisdom was to treat only active disease, since in most persons the infection would be dormant and not a threat to themselves or others. The current wisdom is that some of the cases of latent disease would become active disease and further even latent infections could spread disease- albeit at a much lower level. Of course, some would also clear the infection spontaneously- but models were showing that there is a net advantage to the End TB goal if all those with latent infection could be detected and treated. One notes that PTT is not altogether a new strategy, since there was a recommendation that children below six in contact with tuberculosis patients should be put on INH prophylaxis. Practitioners of the earlier generation remember it as a much-contested recommendation seldom followed by paediatricians. The current recommendation is to test latent disease in all family members or neighbours in close contact with a person with active disease and treat all those found positive irrespective of symptoms. This calls for an enormous increase in testing and a significant increase in treating a large number of persons with no symptoms whatsoever. In regions with low access to molecular testing, treatment is started off without testing in asymptomatic cases- but there is a risk that some of them could be active. Further In high incidence settings, the protective effect of preventive therapy is transient – given the high likelihood of future re-infection – but has value in young children and those with HIV. Preventive therapy is also unlikely to be effective where there is antibiotic resistance in the source case. There are regimens for contacts of drug resistant cases, but if resistance in source case is not known, then the appropriate PTT is difficult to decide. The PTT strategy would work only if there is high coverage of PTT going simultaneously with control of high transmission active cases. (4) (GJ Fox, 2016)

Scaling up PTT – the challenges: One challenge is to persuade all contacts to consent to be tested and treated and then ensure compliance with a full course of medication. Contacts should not be put on treatment based merely on history of contact. Some of them would have active disease, even if sub-clinical and these need a full course of treatment- and not just a one or two drug regime. If active infection is missed and such patients put in treatment, the chances of drug resistance emerging would be more. Another challenge are the widespread reports of shortages of the new drug being introduced for PTT- a drug that was expected to make compliance much easier.

PTT and Universal NAAT: This recommendation for such widespread PTT is based on the premise that testing with NAAT would become universal. But currently only 36% of patients are accessing this diagnostic. Though it is being rapidly scaled up there are huge problems in doing so- including availability of reagents, rising prices of cartridges and chips, quality assurance and the establishment of NAAT capable diagnostic laboratories at every block or even more peripherally. All of these have huge budgetary implications, and at a time when public health services budgets are almost stagnant in real terms, the question is as to what services the introduction of such treatment displaces. Further in a situation where over 60 percent of those with active clinically overt disease are being missed, to achieve a significant detection of those with sub-clinical and latent forms is truly ambitious. And if resources are a limitation, then this would be poor prioritization.

Active Case Finding: Another question we need to ask is whether these new technologies are addressing the main gaps the program is facing. As per prevalence surveys (from India for example) as many as 64 per cent of those with symptoms and active disease have not sought care. Case detection and notification has been consistently low over the decades. In recognition of this problem, the strategy now recommends active case finding that would include extensive use of X-rays and NAAT testing for anyone with the symptoms. This is a major reversal of earlier strategy. Practitioners would remember that in earlier decades, both active case finding and X-ray diagnosis were actively discouraged as part of the DOTS strategy that was then being promoted world-wide from 1997 to almost 2010. (5)(RNTCP, 2022) The discourse in those years emphasized that it would be adequate if treatment completion was ensured in those with active disease and sputum positive. (6) (Dye, Christopher, 1997, Rosella Centis, 2017). Case detection in those who were not likely to complete treatment was in fact seen as a problem to be kept out of the intermittent short course DOTS regimes. When the call came to abandon intermittent regimes in favour of daily regimes and insist on treating sputum negative cases also, there was considerable resistance from line department officials who had come to believe in the DOTS doctrines as absolute truth. (Sundararaman,2023). Even then active case finding did not gain prominence. Now with prevalence study showing very low case detection, active case finding is back. There is even a target on so called “missing cases”- to denote the number of positives who are predicted but not yet detected. Active case finding often takes the form of sporadic outreach activities using mobile vans and household surveys to chase these missing cases. But this is not enough. Early detection is far more likely in a household linked to a primary health care team and receiving regular visits from a team member. This should go along with intensified case testing done in all like co-morbidities and a higher index of suspicion for TB in all chest symptomatic across public and private providers.

Integration with comprehensive primary health care: The declaration correctly highlights how addressing TB requires UHC and resilient health systems built around universal primary healthcare. In paragraph 49 it commits to “ integrate within primary health care, including community-based health services, the systematic screening, prevention, treatment and care of Tuberculosis and for related health conditions, such as HIV and AIDS, viral hepatitis, undernutrition, mental health, non-communicable diseases including diabetes and chronic lung disease, tobacco use, harmful use of alcohol and other substance abuse, including drug injection, as well as a people-centred, approach, to improve equitable access to quality, inclusive, affordable health services with effective referral systems to other levels of care” This is well articulated- but it implies that achievement requires a universal comprehensive primary healthcare which reaches out to every individual and family in the community and has the capacity to deal with this entire range of diseases. . In particular all poor and marginalized households should be receiving regular house-visits of a primary care team- in other words universal care. If active case finding is done as stand-alone vertical exercises without significantly increasing human resources and finances it would lead to a shift of resources from comprehensive primary health care. Such a shift would be a set-back to both UHC and to TB elimination objectives.

One must also caution that comprehensive PHC is not only primary level care but the entire healthcare system with the primary provider acting as an entry point. Much of the diagnostics would be available at secondary levels. Even for mortality reduction, studies have shown that timely, protocol based, good quality hospitalization in sick tuberculosis cases can reduce mortality significantly. There are studies establishing this,(Hemant Shevade, 2023) and India has made this part of its national strategy. However, this is not yet a part of the global policy discourse.

Action on Social Determinants: While the political declaration full acknowledges the role of social determinants, it has little to say on how to address this. The recent RATION study (A. Bhargava, 2023) has renewed and reiterated the importance of nutrition supplementation to the patient and the family to support cure in the affected, and prevent active disease in the rest of the family. The challenge is of how to take it to scale, in a measurable effective way. As compared to the position in earlier programme versions that nutrition makes no difference (7) (RNTCP Annual Report, 2001), the current roll out is making some efforts to address this. One route is through a monthly conditional cash transfer during the treatment period which has positive effects on completion of treatment but little data on outcomes. (Anupama T). Another is nutrition supplementation for those with low BMI. However, the latter is not on scale and it would be worth following up on this. Determinants like air pollution, especially indoor and outdoor air pollution also require successful scalable models. The missing social determinant in the global policy discourse is occupational health- which is a major proximate determinant that allows for considerable primary and primordial preventive action.

Action on Financial Hardship: Implementing a universal, accessible and equitable comprehensive primary healthcare system can significantly reduce the direct treatment costs borne by individuals and families through out-of-pocket expenditures. However, it does not alleviate the financial challenges resulting from income loss, which constitutes a crucial and substantial indirect cost for patients and their households. To effectively address this issue, it is imperative to implement a range of income replacement schemes and social protection programs. (Tanimura et al., 2014).

Models and Modelling

Given these challenges, any impression created by the WHO and UN Nations declarations, that we are in last mile of addressing this disease would be seriously misleading. Much of the new strategies are justified by modelling. The assumptions on which these models are constructed are not readily accessible and are not within the capacity of most countries and most of civil society to comment on. In practice, they require to be taken on trust as evidence-based conclusions and are often construed as scientific facts, when on the contrary assumptions are often judgement calls taken on a chosen framework of analysis.

This current Global Plan states that it has used a “normative approach”, to constructing the model wherein the projected implementation of tools (e.g., diagnostics, medicines) and services (e.g., patient support) are consistent with WHO guidelines. (Global Plan, 2022). This approach was justified on the basis that it allowed for more detailed projections of resource needs. This contrasts with earlier approaches where models also factored current levels of program effectiveness and utilization. We know that a universal implementation of WHO guidelines is clearly not possible in many countries and in all countries, given the financial and health systems constraints they face. In areas like access to diagnostics and medicines, implementation needs significant changes in global policy on patents and manufacture. These reforms are flagged by the political declaration, but WHO itself has made little headway in securing the necessary reforms or raising the necessary resources. In the absence of such policy changes, there would no doubt be a major publicly funded utilization of these new technologies on the scale of the covid response and with it a similar pattern of profits to global pharma- but it would not be associated with the same decline in the disease as the Covid pandemic experienced. However, if the call for elimination of tuberculosis program carries with a renewed thrust to act on its social determinants and brings additional resources and efforts to strengthening comprehensive primary health care, instead of displacing existing services – then that would be a major gain.

Acknowledgements: Thank the peer reviewers who have also contributed to developing this article: Dr Hemant Shewade, Dr. T. Anupama, Ms. Kirti Tyagi, Dr Ganapathy Murugan.

References:

- United Nations General Assembly, Political declaration of the high-level meeting on the fight against tuberculosis; A/RES/73/3 adopted by the United Nations General Assembly on 22nd Sept, 2023

- Stop TB Partnership, The Global Plan to End TB 2023-2030;; Geneva, 2022

- United Nations, SDGs 2023 Special Report, page 18 https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2023/

- J. Fox; C.C. Dobler, B.J. Marais, J.T. Denholm; Preventive therapy for latent tuberculosis infection—the promise and the challenges, International Journal of Infectious Diseases 56 (2017) 68–76

- Central TB Division RNTCP Annual Report (2002).

- Dye, Christopher, et al. “Prospects for worldwide tuberculosis control under the WHO DOTS strategy.” The Lancet 352.9144 (1998): 1886-1891.

- Rosella Centis and Lia D’Ambrosio; Shifting from tuberculosis control to elimination: Where are we? What are the variables and limitations? Is it achievable? International Journal of Infectious Diseases, Volume 56, March 2017, Pages 30-33 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2016.11.416

- Sundararaman, personal communication, based on experience as executive director of State Health Resource Centre, Chhattisgarh 2002 to 2007 and of National Health Systems resource Centre, 2007 to 2014. (also refer peoples health movement publications)

- HD Shewade, G. Kiruthikab*, Prabhadevi Ravichandrana*, Swati Iyer, Quality of active case-finding for tuberculosis in India: a national level secondary data analysis,GLOBAL HEALTH ACTION 2023 VOL. 16, 2256129 https://doi.org/10.1080/2023.2256129

- National TB Prevalence Survey in India 2019 – 2021 :: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (tbcindia.gov.in)

- A Bhargava, , G Sai Teja et al Nutritional support for adult patients with microbiologically confirmed pulmonary tuberculosis: outcomes in a programmatic cohort nested within the RATIONS trial in Jharkhand, India Lancet Glob Health 2023; 11: 1402–11 August 8, 2023; https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(23)00324-8

- Bhargava, Madhavi Bhargava, Ajay Meher et al. Nutritional supplementation to prevent tuberculosis incidence in household contacts of patients with pulmonary tuberculosis in India (RATIONS): a field-based, open-label, cluster-randomised, controlled trial. The Lancet, Volume 402, Issue 10402, 19 August 2023, Pages 627-640

- Hemant Shevade et al, The First Differentiated TB Care Model From India: Delays and Predictors of Losses in the Care Cascade, Global Health: Science and Practice April 2023, 11(2):e2200505; https://doi.org/10.9745/GHSP-D-22-00505

- Tanimura, T., Jaramillo, E., Weil, D., Raviglione, M., & Lönnroth, K. (2014). Financial burden for tuberculosis patients in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review. The European Respiratory Journal, 43(6), 1763–1775. https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00193413